The Global East and the Subaltern Empire in the Breakdown of Worlds

What is the “Global East” and where does this concept come from? How does Russia’s war against Ukraine transform the very language of describing political reality along with that reality itself? Who can speak this language and how can it be changed? Sociologist Ivan Kislenko explores the intricacies of geopolitical terminology

The concept of a “Global East” critically redefines the rigid conventional division of the world into North and South. The Global East is most often identified with the post-Soviet world and post-socialist countries, and is sometimes associated with the former “Second World”, a Cold War construct that designated socialist countries and their allies. Such use of the concept allows us to outline its boundaries, but does not capture its essence, which amounts precisely to an attempt to avoid such simplifications.

The first time one sees the phrase “Global East”, one may legitimately ask: where is the East? The first thing that comes to mind is to look for it on the political map of the world. But addressing the history of terminological transformations against the background of the current war in Ukraine will reveal that such an approach is not necessarily a good idea.

One characteristic feature of the Global East to be taken into account is its proximity to a subaltern empire, that is, an empire that has colonial ambitions and simultaneously occupies a subordinate position in relation to the Euro-American world: Russia. In this sense, the idea of the East emerges from a simultaneous similarity and difference with the Global North. If we accept the strategy of “strategic essentialism”, in which diverse oppressed groups solidarize on the basis of similar identities in order to express common interests, we can notice a growing tendency to declare such similarities in the Global East beyond the subaltern empire’s influence.

Discussing the correlation between the concept’s content and geopolitical reality could further contribute to the expression of interests shared by liminal communities in the North-South dichotomy. The question is the extent to which such a concept actually reflects post-24 February reality and whether it makes it possible to speak, as well as to pursue one’s interests, in the subaltern empire’s shadow. In order to answer it, I will now try to trace the historical circumstances in which the need for such a discussion arose.

The Third World and the Global South

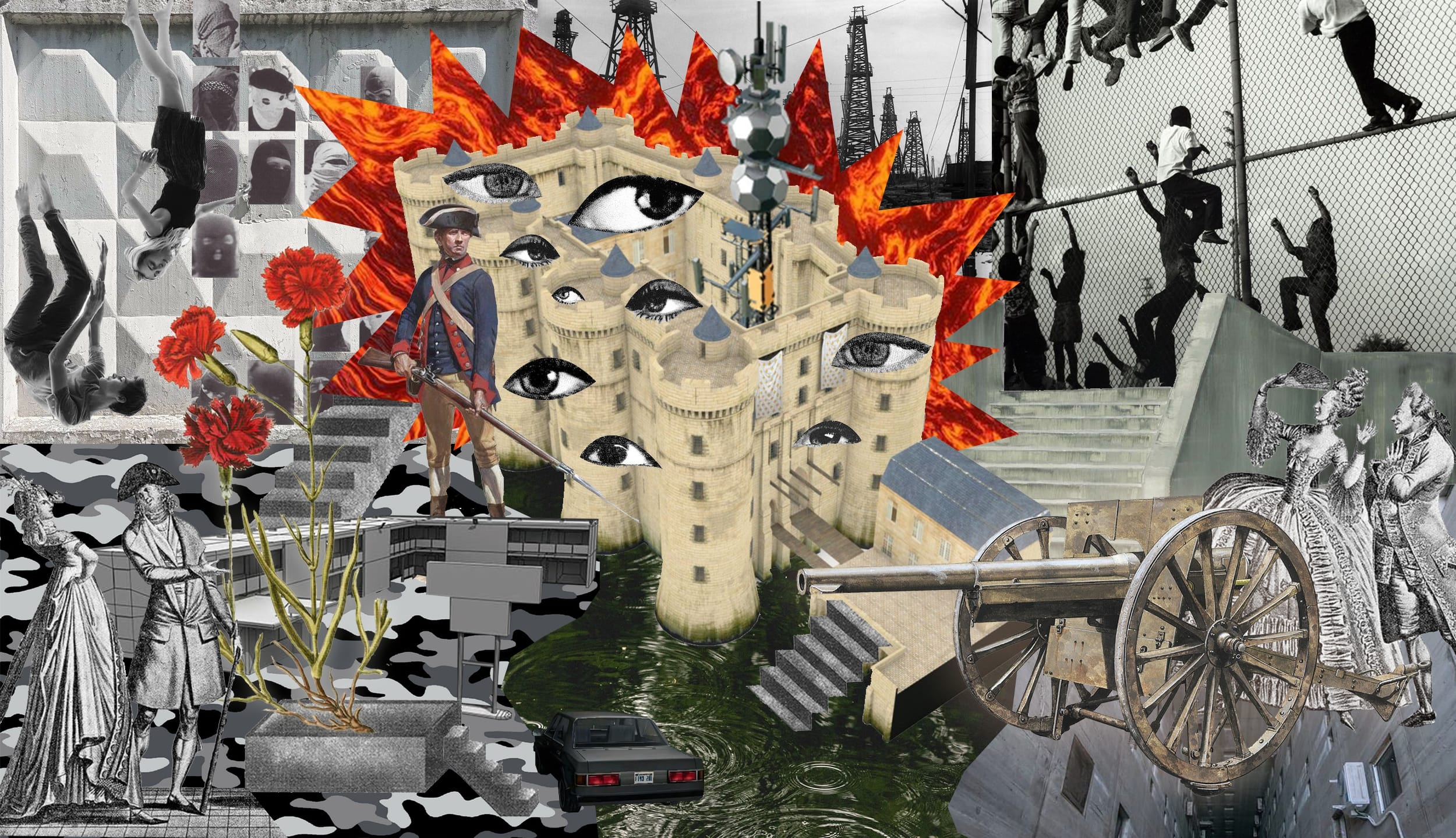

In 1952, the French magazine L'Observateur published Alfred Sauvy’s “Trois Mondes, Une Planète” [“Three Worlds, One Planet”]. In this article, the author examined the confrontation between two worlds, capitalist and communist. The text is the first instance of the term “Third World” being used in its modern sense, to denote the part of the world that did not fit into the binary paradigm of the Cold War. Sauvy drew a parallel between the status of the Third World and that of the Third Estate on the eve of the French Revolution. The voice of the Third World, unheard against the backdrop of the Cold War, aspired to become at least “something” even if it cannot “become everything” per the promises of the Internationale.

Around the same time, the anti-colonial movement was growing in Africa. In 1957, Ghana gains its independence, led by Kwame Nkrumah, a critic of colonialism. The war for independence from French dominance erupts in Algeria (1954–1962). Frantz Fanon, a classic exponent of anti-colonial thought, is a witness to this war. In Algeria he joins the local independence movement and works for the National Liberation Front as a newspaper editor. A year before the end of the war, he publishes the book Les Damnés de la Terre (1961), a milestone of critical literature on colonialism, as well as a unique study of the underlying relationship between the colonized and the colonizer.

1960 becomes “the year of Africa” as 17 countries of the continent gain independence from European colonial powers. The Portuguese colonial war (1961–1974) soon begins, in which modern Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, and Angola fight for their independence. Numerous wars and conflicts occurred when European powers and colonies clashed in the breakdown of worlds.

In 1955, the Bandung Conference held in Indonesia affirms the principles of peaceful coexistence, as well as the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist policies of 29 countries in Asia and Africa. It was followed by the Belgrade Conference of 1961 and the emergence of the Non-Aligned Movement that declared the non-bloc status of an already broader list of participants. These events were designed to frame the Third World as a force seeking closer cooperation among countries and navigating their course between the two poles of the Cold War. The Third World was originally thought of as a political space beyond the confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. Over time, however, the concept has increasingly taken on an economic meaning, effectively becoming a category that unites countries perceived as economically “undeveloped”.

The emergence of the North-South divide owes much to the Group of 77, an inter-state trade association for southern developing countries, established after the first UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in 1964. The group actively worked towards building South-South ties, including cooperation on economic issues and advocacy for a consolidated political position. By the 1980s, the work of the Independent Commission on International Development Issues resulted in the so-called Brandt Line, dividing the world into an economically “developed” North and a “developing” South.

Tom Tomlinson in his article “What Was the Third World” quotes Elie Kedourie’s definition of the Brandt Line as dividing “the world into ‘northern’, rich, exploiting nations and ‘southern’, poor, exploited nations”. The Brandt Line was determined by economic parameters and for this reason zigzagged around the map, including Australia and New Zealand in the North, for example. In Walter Mignolo’s later description, this “socio-economic and political division” marks the United States, Canada, developed Europe, and East Asia as North; while Africa, Latin America, developing Asia and the Middle East are labeled South. Although the Brandt Line is considered an outdated paradigm among scholars today, it has largely served as a basis for the definitions of North and South in further discussions.

As Ulrich Beck notes, the term “Third World” came to be gradually replaced by “developing countries”, which later transformed into “post-colonial countries” and then “Global South” as the preferred term. With the collapse of the USSR and the declaration of the “end of history”, the communist Other disappeared, and the era of confrontation between two political blocs receded into oblivion. The Third World, having become the Global South, now only had the First World, the Global North, as its counterpart. But what happened to the “Second World”?

The Global East and the subaltern empire

Reading scholarly publications and listening to speeches by politicians and economists reveals that the Global North and South are attributed specific traits. The North is mainly used to describe the economically developed liberal democracies of the West, while the South spans economically developing countries that indirectly or directly experienced the policies of colonial powers of the past. The colonizers left behind regions that were largely politically unstable and economically devastated by colonial exploitation. The difficult past has left deep scars on the societies of the Global South, not only economically, but also in terms of politics, culture and values.

In the course of time, after the disappearance of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, the Warsaw Treaty Organization and the collapse of the USSR, the divergence between the gradually emerging new geopolitical reality and the North-South division became more and more apparent. For instance, a number of former “second world” countries could hardly be identified with the Global North. Insufficiently strong in economy and not very stable politically, these countries did not match its definition very well. This state of affairs still persists, for example, within the European Union, where the New Europe (the post-socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe) differs from the Old Europe in many ways. As Martin Müller notes: “Countries may join the European Union, but the subtle distinctions of habitus of Eurocrats in the corridors of power in Brussels continue to mark the difference between the East and the West.”

Likewise, it is difficult to identify these countries (whether post-Soviet, post-socialist or former “second world” countries) with the Global South. Their nominally similar problems with colonialism suggest an affinity to the South, but it is not close enough to say that they are really the South: too “developed” for the latter and not “European” enough for the North, politically and economically.

Despite this very essentialist language, the notion of the Global East has merit, since it emerges as a critique of the North-South division and is an attempt to describe liminal communities in this paradigm. It results from an awareness of the insensitivity of such a division to the diversity existing in the world, which does not fit into the logic of binary opposition. With a number of attributes common to both North and South, the Global East becomes an object of double exclusion from the privileged Global North and from the marginalized Global South. The Global East is both the object of oppression and the subject of its production. Müller, for example, focuses on the fact that many countries of the Global East were colonized, were themselves colonizers, and sometimes were both.

Indeed, it is difficult to identify the Global East fully with the “wretched of the Earth” of the Global South, just as it is impossible to identify it unambiguously with the Global North, which has been actively colonizing the Southern countries. From the above remarks we can conclude that it is possible to define both concepts by means of a political map of the world. Indeed, it is even possible to use the Brandt Line, however outdated it may be, to make an approximate list of countries that can fall into either category. But the very idea of North and South as entities arises from the need to articulate the relationship between them — complicated, burdened by a colonial past and a neocolonial present, it hinges on a complex system of checks and balances, and is held together by subtle issues of power, dominance and subordination. The same is true of the Global East. It always exists “elsewhere” because its geographical positioning is not only difficult, but also inconsistent with the ultimate purpose of the concept’s emergence and use.

Another distinctive feature of the Global East that needs to be mentioned is the presence of a subaltern empire — Russia — on its very hypothetical territory. The subaltern empire is, on the one hand, a colonial empire and, on the other hand, a country that is somewhat dependent on the Global North, which has recently been made evident by sanctions (parallel imports, problems with spare parts for aircraft, etc). Such an empire is two-faced. It feels its dependence on the West-Global North, which it is now allegedly trying to break, while at the same time acting as a “civilizer” of territories that it essentially considers its colonies (as can be clearly seen in the case of Russia's military aggression in Ukraine and the occupation of its territories).

At the same time, Vladimir Putin in his recent speeches (e.g., the Valdai speech) actively tries to appropriate the anti-colonial agenda, presenting his foreign policy as a struggle against the colonial hegemony of what he calls the “collective West” (i.e. the Global North). Putin's ostensibly anti-colonial statements are an attempt to claim the moral right to counter-hegemonic struggle that the anti-colonial Global South possesses. Apparently, reproducing this kind of rhetoric is aimed at laying and reinforcing such claims. Except that these claims are unfounded: they have no content of their own, they do not indicate the source of the moral right itself, and, most importantly, they have nothing to do with anti-colonial narratives.

Can the Global East speak in the subaltern empire’s shadow?

In her landmark article "Can the Subaltern Speak?" Gayatri Spivak discusses the sati ritual (the practice of self-immolation of widows in India) to pose the question: what enables the oppressed to speak about their oppression? In such a situation, there is always someone to speak for them. In fact, no one is interested in subalterns having a voice of their own, otherwise the system of subjugation may break. This includes having a theoretical apparatus that can adequately describe what is happening to the oppressed. Awareness of this fact is the first step toward a reflection on one's own situation, a necessary condition of it.

While the war protracts the logic of aggressive colonial expansion, a number of countries are losing interest in sharing the hypothetical space of the Global East with the subaltern empire. The war is forcing even those whom Russia might previously have considered its allies to pursue a more restrained policy. For example, Kazakhstan, represented by President Tokayev, has repeatedly declared its commitment to a multi-vector policy after the start of the war, and Russia itself has completely ignored Armenia in the context of what is happening in Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh), forcing it to seek other ways out, such as direct negotiations with Azerbaijan.

It is difficult to speak in the shadow of such an empire. Most of the Global East does not want to bind its values, norms, policies and economy to narratives of contesting Western hegemony. Russia’s potential allies are not willing to engage in real support for these narratives beyond the potential benefits that such rhetoric could provide.

As a subaltern empire, Russia has no chance of symbolically embedding itself in the Global South and playing the anti-colonial card against the West. The space of the Global South is imbued with counter-hegemonic and, most importantly, anti-imperial sentiments. This is exactly why the subaltern empire exists in the hypothetical space of the Global East. Its construction is held together not through political unity, not through a similarly structured economy, and not even through the common experience of socialism (as Müller suggests in his article). The Global East is a contradictory configuration of differences and similarities with the Global North. This configuration is cemented, among other things, by the efforts of various countries to emphasize the similarities. These efforts may be unequivocal (the position of almost all of New Europe on the war) or contradictory (the policies of the Georgian Dream party in Georgia), but they fit, in one way or another, into the logic of rapprochement with the West, alias, Global North.

Despite fair criticism of the concept of the Global East for its use of essentialist language, which ascribes a single subjectivity to a whole spectrum of diverse communities (after all, the “unity” of the Global East is largely an assumption) and sometimes leads to excessive “orientalism”, the term is gradually penetrating political language and gaining in popularity. A possible reason for this is that the decolonial narrative, to which outdated Cold War “worlds” have little relevance, is gaining ground again. It emerges out of a confrontation with the colonizer, whether “on the ground” or in a university classroom. Apparently, the need to work with a decolonial lens forces researchers to look for new, more accurate language to describe ongoing developments.

The Global East as a construct invented before Russia’s full scale invasion of Ukraine does grasp the problem of the North-South divide. In the presence of a belligerent subaltern empire and in the absence of a clear desire of all countries to share strategic essentialism throughout the assumed space of the Global East, we need to question the extent to which this construction still corresponds to reality. That said, traces of such essentialism can be observed in the behavior and rhetoric of non-imperial nations (New Europe’s more or less consolidated position on the war, which I already mentioned). Presumably the East could use such a strategy to gain its own voice against the background of the North and the South. However, the subaltern empire’s aggressive military expansionism and its consequences make it impossible to speak of a potential strategic essentialism of the Global East.

On the one hand, the Russian war against Ukraine has emphasized that the Global East can indeed be understood as a space that resists being described in the usual North-South paradigm. On the other hand, the war revealed the reluctance of large parts of the global East to be neighbors of a subaltern empire. Time will tell if and how a new round of reconceptualizing the global East will take place. This depends directly on the course of the war and its outcome, as well as on developments within the subaltern empire.

Of course, the very fact that a critical discussion about dividing the world into North and South is taking place represents a step toward finding a way to talk. This debate amounts to an attempt to grasp ongoing events, and potentially to defend the shared interests of liminal communities in the North-South paradigm. Nevertheless, in the context of war, the hypothetical Global East is once again faced with the problem of separating its subjectivity from the subaltern empire. The latter will likely continue its attempts to extend its influence across the Global East, but the existence of the discussion is already the first step towards that Global East gaining more subjectivity. The need to interpret reasonably the changes taking place in the world today means that the discussion about the Global East, which was based on an attempt to describe geopolitical reality, will continue.

Мы намерены продолжать работу, но без вас нам не справиться

Ваша поддержка — это поддержка голосов против преступной войны, развязанной Россией в Украине. Это солидарность с теми, чей труд и политическая судьба нуждаются в огласке, а деятельность — в соратниках. Это выбор социальной и демократической альтернативы поверх государственных границ. И конечно, это помощь конкретным людям, которые работают над нашими материалами и нашей платформой.

Поддерживать нас не опасно. Мы следим за тем, как меняются практики передачи данных и законы, регулирующие финансовые операции. Мы полагаемся на легальные способы, которыми пользуются наши товарищи и коллеги по всему миру, включая Россию, Украину и республику Беларусь.

Мы рассчитываем на вашу поддержку!

To continue our work, we need your help!

Supporting Posle means supporting the voices against the criminal war unleashed by Russia in Ukraine. It is a way to express solidarity with people struggling against censorship, political repression, and social injustice. These activists, journalists, and writers, all those who oppose the criminal Putin’s regime, need new comrades in arms. Supporting us means opting for a social and democratic alternative beyond state borders. Naturally, it also means helping us prepare materials and maintain our online platform.

Donating to Posle is safe. We monitor changes in data transfer practices and Russian financial regulations. We use the same legal methods to transfer money as our comrades and colleagues worldwide, including Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

We count on your support!

SUBSCRIBE

TO POSLE

Get our content first, stay in touch in case we are blocked

Еженедельная рассылка "После"

Получайте наши материалы первыми, оставайтесь на связи на случай блокировки

.svg)