“War Breaks and Disrupts the Relation between Things”

How is nuclear power getting weaponised? Why in the world of digital technologies are soldiers still put in trenches? Media theorist Svitlana Matviyenko on modalities of war and Russia’s aggression in Ukraine

— In your current work, you refer to and study what you call “nuclear cyberwar.” How did you come to this concept?

— My academic research began with an exploration of digital militarism and online mobilization. The events surrounding the Maidan protests in Ukraine, which I viewed in a broader context, were particularly central to my thinking. In the book I co-authored with Nick Dyer-Witheford we reintroduced the concept of cyberwarfare, which had a long history within military and security circles. However, we sought to reclaim it for discussions of political and economic relations and their intersections with the information economy, which were being amplified by new platforms and forms of connectivity.

Around the same time, after a decade of living in the USA, I made two trips to Ukraine and visited the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. To my surprise, none of the people I knew had ever visited it. Probably due to trauma or because proximity gave them some tacit knowledge about this site. This research was a slow process; I had to live there and carefully approach people.

As you see, I used to keep my work on digital militarization and legacies of nuclear industries as two separate streams. However, after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, when the nuclear power plants (NPPs) were occupied by Russian forces, I identified the new phenomenon “nuclear cyberwar”, that I wanted to theorise.

— What does weaponization of the nuclear mean?

— If you were to research atomic energy and its infrastructure, you would see the complex and convoluted relationships between civilian and military operations and how they can transform one into the other. The atomic industry is a clear example of the intersection between technology and energy. In modernity, this division between the military and civilian, war and peace, symptomatically disappears. Something that looks peaceful has in fact military legacies, and vice versa. And atomic energy is one of the major examples of that. The history of the atomic industry in countries like the UK, USA or USSR hides some shady operations. For example, weapons-grade plutonium [the material used for nuclear weapons – ed.], was produced in places that were thought to be civilian facilities. This legacy remains ever-present, and these links require careful discussion.

People who followed recent events will remember how Russian forces approached both the Chernobyl and Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plants (NPPs). This was a particular technique in the weaponization of nuclear power. The Chernobyl NPP is now a state-run enterprise for decommissioning because it takes years to stop production, but it still contains a plethora of materials, chemicals, and fuels that could cause incredible danger if disturbed. With the Zaporizhzhya NPP, we have all of that, including working fuels, making it incredibly dangerous. On September 11th, 2022, operations at the plant were slowed down, and most activities were stopped for security and safety reasons. But everything that was going on during summer 2022 was absolutely terrifying and dangerous.

Specialists in nuclear energy and former workers, whom I consulted, shared a general assumption that we have never been so close to an absolute catastrophe. The way the Russian forces behaved is hard to define, and there is not a single reason behind their behaviour. Reports suggest a combination of negligence and awareness, knowledge and lack of knowledge among low and high ranks. It might be a chaotic action, a joint spirit, or a combination of both. Zooming out, there are clear reasons to call the exploitation of nuclear power in this manner a form of weaponization, regardless of whether soldiers or other people were aware or not. Weaponization means to create a weapon out of something and use it as a particular action exploited during a war, turning nuclear power into a nuclear bomb.

— At the same time, there’s also an idea of nuclear deterrence that emerged in the 1960s. Nuclear weapons were seen as a means to deter conflict, to prevent or stop actual violence. Nowadays the constant threat of using nuclear weapons seems to perpetuate the conflict. What do you think about that?

— The concept of nuclear weapons being a tool for restraint has always been problematic. We need to reconsider and question this history today. When you look back, people like Margaret Thatcher could not imagine a world without nuclear weapons [note: she once said, “a world without nuclear weapons would be less stable and more dangerous for all of us”]. This is a legacy of modernity, where the line between war and peace becomes blurred. If a weapon with the potential to destroy the planet is necessary for peace, how should we define peace? This paradoxical logic has guided many political decisions in the past few decades. Nuclear weapons were thought to restrict and constrain, but they are questionable and problematic as a means of non-proliferation.

The way the Russian forces behaved is hard to define, and there is not a single reason behind their behaviour. Reports suggest a combination of negligence and awareness, knowledge and lack of knowledge among low and high ranks. It might be a chaotic action, a joint spirit, or a combination of both. Zooming out, there are clear reasons to call the exploitation of nuclear power in this manner a form of weaponization, regardless of whether soldiers or other people were aware or not. Weaponization means to create a weapon out of something and use it as a particular action exploited during a war, turning nuclear power into a nuclear bomb

Although there are some transparent declarations and formats, much of the politics and legacies surrounding nuclear weapons is murky. I recognise that Russia’s war against Ukraine has taken us to a new level because everything that was previously hidden has been exposed, which is what shocks us. But it simply mobilises all the previous symptomatic things and legacies about that. Nuclear weapons are used for bargaining, coercion and threats, but only when it comes to direct nuclear weapons, such as the infamous “red button”. However, there are also tactical nuclear weapons and weaponized nuclear power plants. It is another discussion, which obliges us to differentiate between various nuclear items and tools and to see how they are all employed for the same reasons in a war.

— In this case, what about propaganda? It is often considered that the primary target and victim of Russian propaganda spread through state-run TV channels and social media is the domestic audience. How does it work in respect to the Ukrainian media sphere? However, in your keynote lecture which opened the Transmediale festival in Berlin last year, you argued that this hate speech also serves to terrorise the Ukrainian media sphere.

— TV propaganda is a weapon that is used to address people as enemies in the conflict. As a specialist in cyber warfare, people often ask me about how the Russian government lies to its population and what kind of propaganda exists in Ukraine. However, I find it problematic to put these two things in one conversation because they are not symmetrical. One technique aims to maintain sanity, while the other entices killing.

Russian propaganda is often seen as being contained in one place, but the modern world, according to Zygmunt Bauman, is liquid and everything flows through networks. So various media reach different audiences, including Ukrainian citizens. Russian propaganda indeed terrorises its own citizens, producing a terrible environment, which is very different from what it does to Ukrainian users. No matter how outrageous things are, it is hard to hear someone calling for drowning Ukrainian children [note: ex-RT TV-presenter Anton Krasovsky] or someone like Margarita Simonyan [the head of state television network Russia Today and chief propagandist] thinking she has the right to decide who has to die or live. These phrases leave traces on your consciousness or unconsciousness because you hear the intention to destroy and erase you.

I often think about myself as a reader here. Notwithstanding how ironic my comments might be, there is a subjective dimension that is definitely touched. As a researcher, who had to go through different materials and is seemingly being protected with my analytical knowledge, I get affected by it. And, of course, it reaches the majority of people who are very active on social media or have the urge to engage in conversation, because it is an act of aggression towards their own being. If some genocidal acts happen, many Ukrainian citizens would need to defend themselves and say that the information about strikes or murders is not fake but is, in fact, contrary to how it is presented on Russian TV. While I recognize the way it is done towards the Russian population, we need to equally recognise these loops of terror and aggression outside of that country.

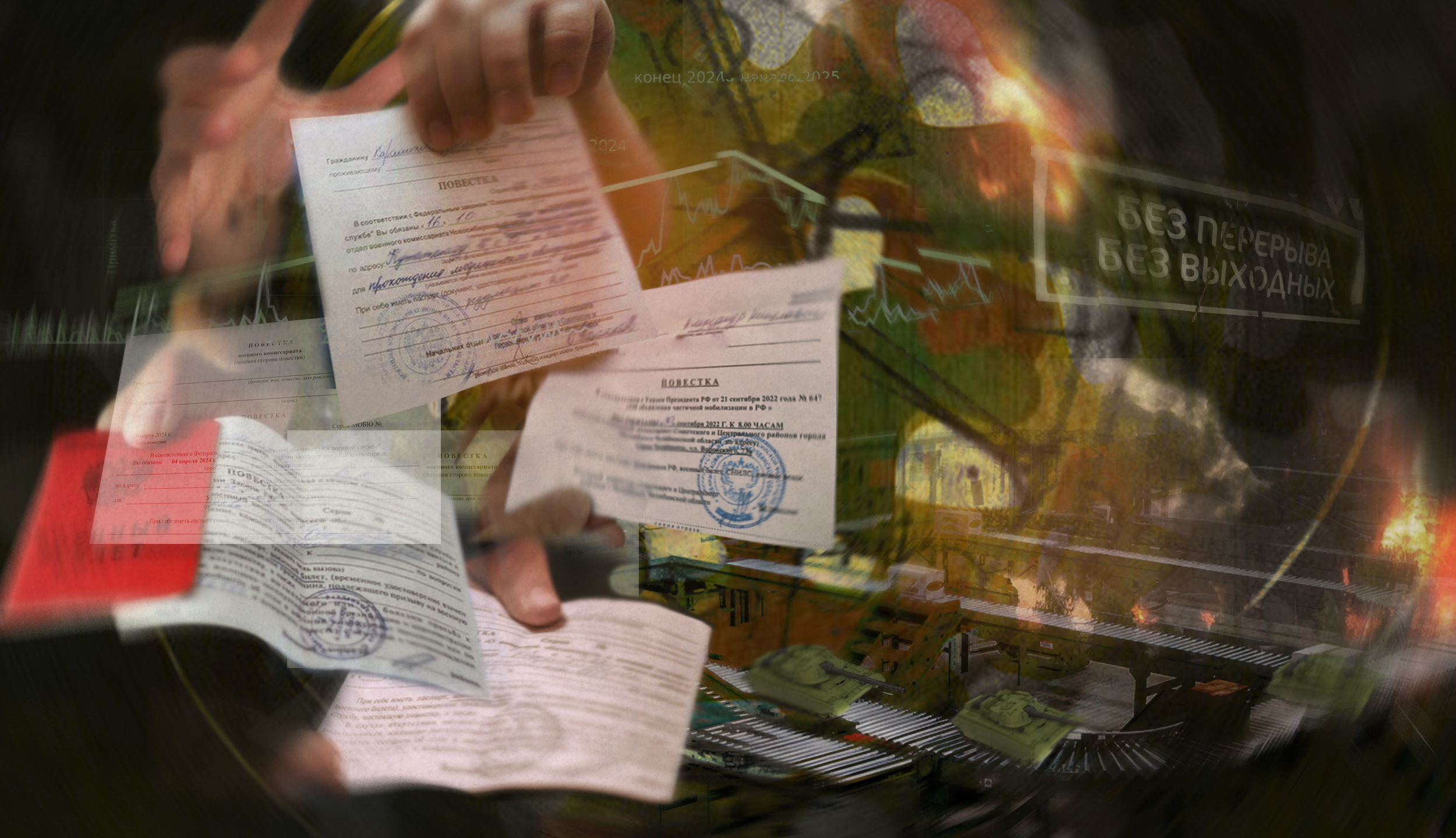

— Philosophers sometimes speak of the brand-new modality of war, guided by new technologies like autonomous bombs and intelligent missiles. The current conflict, nonetheless, seems to be a mixture of weapons: WWI, WWII and imaginary WWIII: we see the attacks in cyberspace, drones altogether with mud and dirt of the trenches. Why do you think it is so?

— This knowledge on how wars are conducted is not necessarily linked to a particular [historical] time. Previous wars have influenced the strategies employed in subsequent conflicts, etc. There was a tendency shared by some scholars and speculative thinkers who saw the war as an expression of a stage of technological development: if it is cyber, then it should be entirely done by digital technologies. This argument that “cyber war is just done by digital technologies” should entirely disappear. I think good Sci-Fi movies have a better understanding of this phenomenon than some scholars. In Blade Runner (1982) we see the total decay of the unfolding Anthropocene, the climate crisis and high-tech technologies at the same time. The dirt and mud of the trenches, artillery, technologies of prediction, aeroplanes, digital technologies, all in one frame.

If some genocidal acts happen, many Ukrainian citizens would need to defend themselves and say that the information about strikes or murders is not fake but is, in fact, contrary to how it is presented on Russian TV. While I recognize the way it is done towards the Russian population, we need to equally recognise these loops of terror and aggression outside of that country

These assemblages do not exclude any technology, but rather they become more and more complex. The modern war utilises all available means and sometimes when I hear this phrase “war by all means”, I do not think about the present moment, but think backwards in time and imagine all the means available in WWI, WWII and so on. However, there are limits in terms of how wars are maintained, so I would still see it in terms of modernity. It has to do also with what I was saying in the lecture, following Peter Sloterdijk, who speaks of environments. In the 20th century wars ceased having particular targets, what was rather targeted in those atmospheric or “environmentalized” wars are the relations. The modern war breaks and disrupts the relation between things, it decomposes those assemblages that sustain peaceful life. This is what really keeps different wars of the 20th century [and the wars of the 21st century] in one framework.

— The current armed conflict is often described as the most documented and mediated in human history. How does this total transparency, when testimonies are so hard to hide, impact warfare and the so-called “fog of war”?

— There are several questions to consider here, starting with the scale of available data. Practically every action can now be expressed as a data point, and information can be found online about almost anything. This has led to a race in citizen journalism and open-source data investigations. However, transparency is not enough; it is only when all of these data points are brought together that a bigger picture emerges and the relationships between different events can be understood. On one hand, the unprecedented amount of data available is helpful in producing evidence of war crimes and making claims about what is happening. On the other hand, the sheer volume and complexity of the data can be overwhelming and beyond the capacity of humans to fully process and make sense of it.

Another question is how to deal with this amount of data and what impact it will have on future trials. Specialists say that it is incredibly difficult to present something as evidence or proof in court. One thing is general knowledge, that is where we clearly see the impact of all these records, because it makes us all aware of what is happening. But in court most of those things will not work. It is hard even to bring to court those propagandists who entice the killing, as long as you will need to prove that someone’s particular crazy claim is related to a particular crime. Thus we should distinguish here between juridical understanding of genocide and political genocide.

When one thinks about terror environments, they are situated in this huge gap between political understanding of genocide and understanding of genocide by law. Regardless of how this war will end, we will see only a few criminals punished. The law is incredibly conservative and slow. Even after WWII, there were only 24 people punished following the Nuremberg process.

At the same time, even this awareness and understanding itself is also important enough. Responsibility has many dimensions, even if someone did not participate directly in the conflict. Processing and facing former historical crimes, for instance, those committed during Stalin’s time, is a major task for the country. Therefore, these data would serve to change thinking and understanding and help to recognise this responsibility. Even if someone did not take part in it directly, this responsibility has many dimensions. I hope the documentation, these data points and records would help Russian society to rethink itself and recognise what it has done. Rather than focusing solely on punishing a few individuals, it is more important to change the country’s attitude towards post-Soviet countries and other communities that are now part of the Russian Federation.

— Some present the current conflict as an opposition between Russia and the United States, thereby leaving no agency to Ukraine; others consider it as a conflict between the United States and China, where both post-Soviet countries are just mere puppets. In contrast to these two visions, you suggest seeing two axes of the same conflict: inter-imperial and imperial. How does this second non-communicable vector affect our understanding of war as a “bargaining table”?

— Those who view the current war as either multiple wars or a single war tend to focus on one core reading, while considering everything else as completely secondary. This is an old-fashioned way of thinking that has been inherited from pre-modern times. Wars are overdetermined and it is essential to define specific dimensions or axes to understand them better. Of course, this is also a simplification, but you need to dismantle it, to see how all these dimensions actually come together to such an extent that it becomes difficult to distinguish between them. I have been working on tearing them apart to produce a model that helps understanding, but more research is needed to examine how these dimensions intermingle.

Processing and facing former historical crimes, for instance, those committed during Stalin’s time, is a major task for the country. Therefore, these data would serve to change thinking and understanding and help to recognise this responsibility. Even if someone did not take part in it directly, this responsibility has many dimensions. I hope the documentation, these data points and records would help Russian society to rethink itself and recognise what it has done. Rather than focusing solely on punishing a few individuals, it is more important to change the country’s attitude towards post-Soviet countries and other communities that are now part of the Russian Federation

Speaking about Ukraine and the Russian Federation, the dimensions I identified are imperial/colonial. This particular power relation and mindset shape the impossibility of seeing through the borders on the part of the imperial agent. As many emphasise today, the Empire does not know borders, or “Empire ends nowhere”, as this expression says.

So, the first axis is inter-imperial. Coming back to the practice of deterrence, which has to do with supplies of nuclear weapons and has a Cold War legacy, it became clear to me that deterrence is a particular form of communication. Communication involves moving somewhere, listening to each other, even if it may be accompanied by aggression. What we constantly hear from the Russian side, is this constant insistence on the non-existence of Ukraine. Ukraine is seen as a platform, a resource.

If we look at the areas that are currently occupied or where the front line is set at the moment, these are precisely those territories that belong to the Russian Imperial myth: Grigory Potemkin once went there, kind of expanding Catherine II’s Empire, etc. The imperial view is all about seeing certain territories as empty, as no one’s land, since that is what precisely was happening during the imperial expansion at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. Several centuries of development are not recognised and so easily erased.

Many people in the world think that Ukraine and Russia should negotiate. However, when you listen to the Russian propaganda narratives, when you see Putin openly killing his opponent to win the election, it becomes clear that there is no intention to communicate with anyone who is Ukrainian. The aggressor will never negotiate with those against whom he leads a genocidal war: by doing it, the aggressor has already set the irreversible scenario and it could not be turned towards some sort of negotiations. The only direction for it is the Hague tribunal and the task of Ukrainians now to survive as a nation and a country until the slow process takes place in the ICC. Non-communication has to prevail to make this war look somewhat successful. While people talk about victory and loss, I believe that communication itself is what loss looks like for the Russian government. Those who advocated for the so-called “Potemkin” peace [note: meaning fake or facade peace, similar to Potemkin’s villages] probably overlook this crucial aspect and its role in this war.

— It is often considered that any war ends with the peace treaty and demilitarization. Yet, the battlefield affects the surrounding environment that one could call atmospheric terrorism. How does the war continue to operate after the cease-fire?

— In order to describe this, I use the term “virtual occupation”. This idea should help all of us, particularly those in Ukraine, to problematize the end of the war, as its legacies can be just as horrifying as the war itself. Some of them we can already imagine, some we cannot predict. We speak about ecocide, pollution and trauma. When people experience wars, there is a lot of suffering, but when they move back to live a peaceful life, the consequences of war play out in a new and unexpected way for them. Therefore this war remains in cells, in psychology, unconscious, it deeply penetrates living and nonliving matter. And that is what other dimensions of occupation are in. And that is where the other dimensions of occupation come into play. It is terrifying, but we must certainly remain aware of it.

Interviewed by Andrey Sh.

Мы намерены продолжать работу, но без вас нам не справиться

Ваша поддержка — это поддержка голосов против преступной войны, развязанной Россией в Украине. Это солидарность с теми, чей труд и политическая судьба нуждаются в огласке, а деятельность — в соратниках. Это выбор социальной и демократической альтернативы поверх государственных границ. И конечно, это помощь конкретным людям, которые работают над нашими материалами и нашей платформой.

Поддерживать нас не опасно. Мы следим за тем, как меняются практики передачи данных и законы, регулирующие финансовые операции. Мы полагаемся на легальные способы, которыми пользуются наши товарищи и коллеги по всему миру, включая Россию, Украину и республику Беларусь.

Мы рассчитываем на вашу поддержку!

To continue our work, we need your help!

Supporting Posle means supporting the voices against the criminal war unleashed by Russia in Ukraine. It is a way to express solidarity with people struggling against censorship, political repression, and social injustice. These activists, journalists, and writers, all those who oppose the criminal Putin’s regime, need new comrades in arms. Supporting us means opting for a social and democratic alternative beyond state borders. Naturally, it also means helping us prepare materials and maintain our online platform.

Donating to Posle is safe. We monitor changes in data transfer practices and Russian financial regulations. We use the same legal methods to transfer money as our comrades and colleagues worldwide, including Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

We count on your support!

SUBSCRIBE

TO POSLE

Get our content first, stay in touch in case we are blocked

Еженедельная рассылка "После"

Получайте наши материалы первыми, оставайтесь на связи на случай блокировки

.svg)